Before we launch into what we might learn in history, I’d like to spend a bit of time discussing how we go about learning history. A lot has been written on historical thinking, or thinking like a historian, but most of us are not going to be historians and still need to develop a framework for understanding historical information and putting it in context. I’m going to try to show what I think happens when we learn history. What follows is based on a little bit of information processing theory (as I understand it), a fair amount of experience, and a bit of intuition, so bear with me.

Even though some people claim to love history, and the popularity of history-based television and movies, as well as the steady stream of mass-market history books suggests that this is true, I doubt that most of us have given much thought to what we are actually doing when we learn history. Although I have no proof of how the brain actually works when we learn, I suspect that when we learn new historical information, the process is one of schema building and elaboration.

A schema is like a framework of ideas or knowledge about a topic. Some schemas can be really simple, such as our framework for understanding that when the temperature drops, the days get shorter and the leaves fall off deciduous trees, we’re experiencing autumn. Under this schema, “autumn” means lower temperatures and shorter days than what we felt in the summer and the trees go from green to red, yellow, brown and eventually leafless. For many of us, that’s enough to know about autumn, but if learn more about it, what seems to happen is a process of elaborating upon that basic schema by adding new information in relation to the existing information, and possibly discarding information that now seems less probably true. To stick with autumn, we might add to our schema the information that it runs from the autumnal equinox to the winter solstice, and that these dates are usually around September 21st and December 21st. Further elaborations would include the role that the earth’s rotation and revolution play in our experience of the season, and that another word for “autumn” is “fall.” The key thing to remember here is that for the phenomenon of autumn, we each have a schema that represents our understanding of what “autumn” is.

The same process of building and elaborating upon a schema happens when we learn history. Since I don’t know how memory works in the brain, I’m going to try to make sense of this through an illustration, starting with a piece of historical information that I hope most of readers “know,” that in 1492 CE, Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain and discovered America.[1]

The diagram above represents a simple schema for historical knowledge of Columbus. Most readers probably remember the rhyme: “In Fourteen Hundred Ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” so the date “1492” and the act of Columbus sailing across the (Atlantic) ocean are placed as a single, central idea. On the left are subsidiary details that we might or might not remember, such as the name of the three ships he led on his first voyage and that Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain were the sponsors of his mission. I might have included other even less important details like the fact that Columbus was and Italian from Genoa, or even incorrect information, such as the false notion that most Europeans believed that the world was flat and only Columbus was brave, or foolish enough to assert it was a sphere.

On the right side of the diagram I have included information about where Columbus sailed and the results of his encounters. Hopefully most readers will have noticed that at least two of these details are factually incorrect. Columbus had nothing to do with the large empires in North and South America, here referred to as the Aztecs and Incas, although these people were eventually defeated militarily by Spanish military explorers, called conquistadors after the fact. Columbus did land in the Caribbean and establish “settlements,” a term that deliberately underplays the violence and destruction involved in colonizing the region.

Below the main idea are two major consequences of Columbus’s “discovery” that I expect everyone knows. That they are results of the “discovery” is indicated by the arrows pointing to them. Although the precise number of deaths of native peoples in the Americas is highly controversial, it is certainly in the millions and some estimates suggest that 90% of the native population perished as a result of contact with Europeans. I have designated the consequence, “Europeans settle in the Americas” as a blockbuster event or phenomenon by picturing it as an explosion to set it apart as information that is common knowledge, even if we don’t necessarily consider it a direct result of Columbus’s actions.

Before moving on to how we might elaborate on this schema through learning some history, I’d like you to ask yourself if this schema is familiar to you. Are there things in it you didn’t know or didn’t associate with Columbus? If there are other things that are missing, take a minute to write them down or, even better, print out the diagram and write directly on it. When you finish marking up the diagram, consider this question: How did I learn this information? If you can answer that question, you have a better understanding of your own historical thinking than I have of mine. I generated that diagram completely from memory (including the mistakes) and for the life of me I can’t tell you where, when or how I learned it. This to me is a crucial aspect of learning history that can make it easier but usually makes it much harder. Most of us have versions of historical events and phenomena that are deeply wired into our memories. Often these take the form of narratives which cause their own problems that I’ll deal with in another post. The main point is that learning history often involves a process of unlearning things that are stuck in our memories and we don’t even know how they got there.

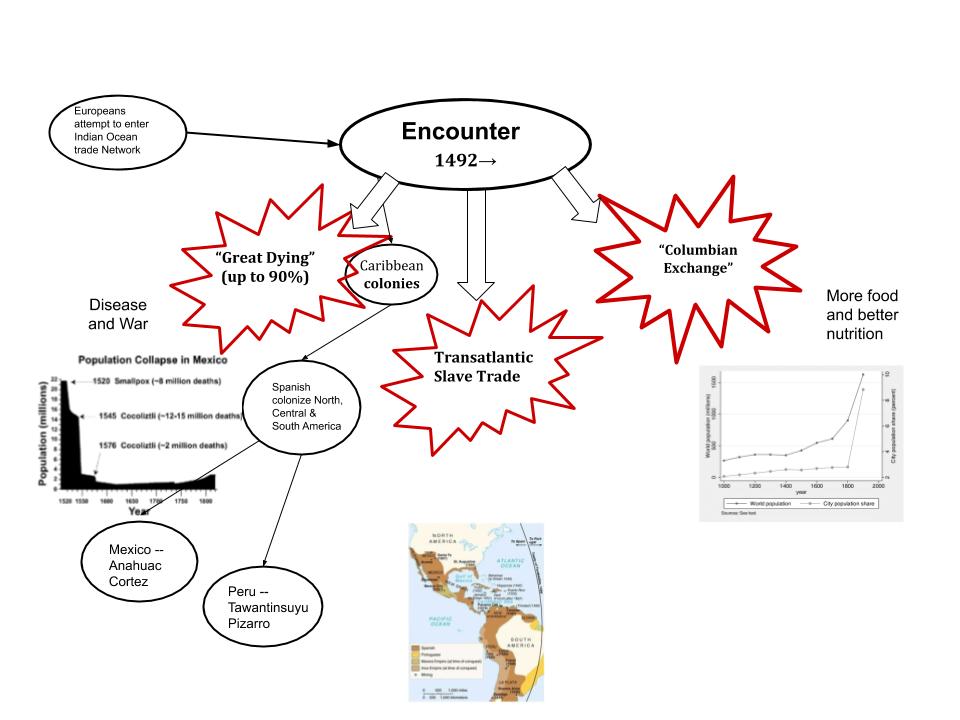

To consider the role that unlearning plays in elaborating our schemas, look at this second diagram, which could represent our how our understanding of Columbus and the encounter between natives and Europeans changes after having some history instruction.

Columbus is still central here, but we’ve replaced his “discovery” with a more equitable term, “encounter,” providing a greater degree of agency for the natives, who have done as much discovering of Europeans as being discovered by them. Ferdinand and Isabella also remain, but now they have been given more context. Rather than simply hiring the adventurous Columbus, they now have a reason to do so. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted a piece of the action that was the lucrative trade that existed in the Indian Ocean.

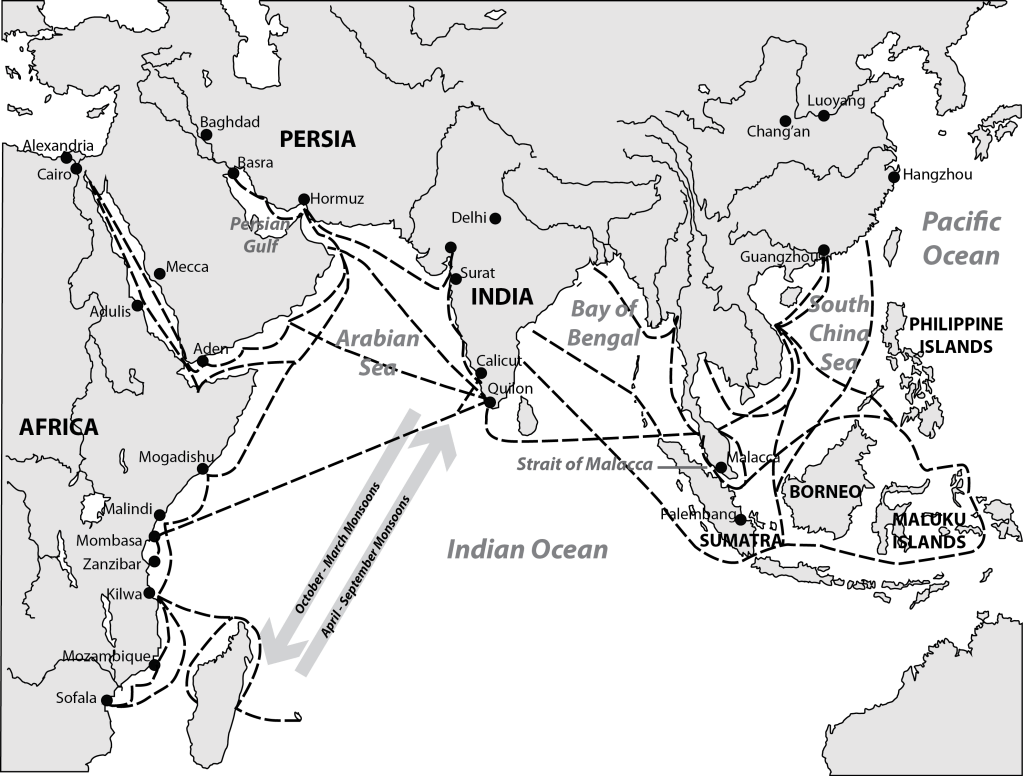

By the end of the 15th century, Europeans, mainly the Portuguese who were the first to sail around the southern tip of Africa, had finally been able to enter the vast and lucrative Indian Ocean Trade Network. For centuries, primarily-Muslim merchants had dominated the trade in this region that stretched from the eastern coast of Africa to China with India as its central fulcrum. Crucial to this trade were the spices produced in the islands to the south of mainland South East Asia, known as the East Indies. This trade would later fall into the hands of the Dutch, but at the turn of the 16th century the Portuguese were in charge, and to such an extent that the Spanish crown took the risk of sending Columbus westward in search of a route to the Indies that didn’t involve sailing all the way around Africa. It was the wealth of these “spice islands” that Columbus was hoping to find when he set sail, and his prior knowledge of them likely explains his initial confused confidence that the Caribbean Islands – the West Indies – were the East Indies that he was looking for.[2]

Columbus realized relatively quickly that he had not found the East Indies, but rather a new set of islands in the western hemisphere. He made multiple journeys to these islands, eventually enslaving native people and sending them back to Spain and convincing the monarchs to make him governor of one of the colonies that was established. These colonies never produced the revenues that the Spanish crown hoped for, and Columbus himself was a pretty poor manager. His voyages only truly paid off after 1519, when Cortez set sail from the colony of Cuba and through ruthlessness, brutality and more than a bit of luck, was able to topple the Anahuac empire that had been established in the environs of Tenochtitlan.[3] In 1532, Spanish troops under Pizarro managed to conquer the divided empire of Tawantinsuyu[4] in Peru and within thirty years the Spanish colony there was producing vast amounts of silver that Charles V and his successors used to finance a series of wars that did little to enhance Spain’s position in European politics, but did a lot to bankrupt the Spanish crown.

Mexico and Peru, which are pictured in the map to the left of the diagram, did have gold and silver which enriched the Spanish, but its agricultural production was probably more important in the long run. The Americas were the source of two foodstuffs that would revolutionize diets in Europe, Africa and Asia: potatoes and corn. It’s difficult to pick which of the two matters more. Corn is used to feed both animals and humans, so it probably gets the edge, but given how potatoes feature in cuisine from Germany to Italy to India, and the fact that they can in a pinch provide enough nutrition to sustain humans for quite some time, it’s a close call. Because it is such good animal feed, growing corn led to an increase in the production of beef and pork, and meat-eating became relatively common for a much larger cross-section of people, especially in Europe. The combination of meat, corn and potatoes greatly increased the number of lower-cost calories available to everyone regardless of class, and improved nutrition led to increased life-span and ultimately to population growth, especially in Europe, but also in India and Africa.[5],[6]

There’s a horrific flip side to population growth in Europe, though, and that is captured by the other major result on the diagram, the Great Dying. The death of native Americans appeared in our initial schema for Columbus, so the change of name and emphasis represent a revision of our understanding, a slightly different type of elaboration than the additions and subtractions we have been discussing to this point. The Great Dying is the term that many world historians now use to describe the devastating losses suffered by native Americans, mostly from diseases like smallpox to which they lacked immunity, but also from war and the brutal conditions that they were forced to endure on Spanish plantations and in mines. It is quite difficult to determine with confidence the numbers of people that died, but it is surely in the tens of millions, and the death rate for natives was anywhere between 25 and 90%.

But the horror doesn’t stop there. European colonizers didn’t move to the Americas en masse. The initial number of colonizers was small, and they needed people to work on the farms and in the mines that helped to make the colonies economically valuable. Initially they attempted to enslave native peoples and they had some success with this, but that success was limited for a variety of reasons, chiefly because so many of the native people were dying. To find another source of forced labor, the Europeans looked to Africa, and thus began one of the most terrible and horrific phenomena in world history, the transatlantic slave trade.

To try to discuss the transatlantic here would do it too great a disservice, and it will be coming up in future posts (and activities)[7]. At this point it’s enough to say that this was one of, if not the greatest tragedies in world history, with profound repercussions that echo down to this day. The key point to take away here is that it was a direct consequence of the encounter between Native Americans and Europeans and that without the transport of millions of Africans to the Caribbean, South, and North America, the world would be a completely different place.

By this point, our view of the encounter has shifted completely. Columbus no longer seems so important at all. The story is now one of colonization, destruction and, for the Europeans, the beginning of a path to population growth, increasing wealth, and, eventually, political domination over large areas of the globe. The most important results of the encounter are the deaths of millions of Native Americans and the destruction of their cultures by Europeans who colonize their land, the Columbian Exchange, and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. This updated schema is represented by the diagram below.

I’m sure you can see how different this newly elaborated understanding of the encounter is. Columbus is now out of the picture, as are Ferdinand and Isabella. We have some visual representations of the cost in lives in the Americas and the growth in world population that resulted from the new foodstuffs being imported into Europe and beyond. The destruction of the Anahuac and Tawantinsuyu states are still there as examples of European colonization. I decided not to elaborate on the transatlantic slave trade because that topic is so big and important that to add details to this thought diagram would overwhelm the original point. It’s as if you started talking about the rules of your favorite sport (for me that would probably be basketball) and tried to illustrate it with a discussion of the greatest team of all time. Both topics deserve attention and discussion and to try include one within the framework of the other will tend to diminish it because we can only attend to so many details without our understanding becoming overcrowded and confused.

This seems to be a good place to stop this particular discussion before it becomes unwieldy. My hope is that this essay provides a model of thinking about how we learn history that takes into account both what we and our students already know as a foundation to build upon. To add one more metaphor, learning history is like building a house. You start with a central plan and add rooms as your needs grow[8]. Sometimes you have to renovate the old rooms, maybe knocking down walls to make it easier to navigate, or adding a new nursery, or enlarging the doorways to make it easier for people with disabilities to feel welcome. As the metaphor suggests, learning history is a process of constructing, revising and re-constructing understanding, and sort of like creating a home, it’s never really finished.

[1] Now some readers will protest that Columbus didn’t discover America because it was already there and had its own rich history. I fully agree, and I will get to that, so bear with me. Trust the process.

[2] In the initial version of the story that you probably learned, Columbus may have thought that he had reached China, but it is unlikely that he would have made this mistake. Europeans had known about China for centuries before Columbus made his voyages, with the writings of merchants and adventurers like Marco Polo having been in circulation since the days of the Yuan Dynasty. It’s never been clear to me why in the Columbus story he’s disappointed not to find gold since the major source of European gold would have been West Africa, and he most certainly knew that he had not landed there.

[3] I’m using the more modern term for the empire that you will still see called the Aztecs or sometimes the Triple Alliance. This is another example of how new information leads us to update our schema.

[4] AKA the Inca Empire.

[5] It probably led to population growth in Asia as well, especially as sweet potatoes entered the Chinese diet as a staple for the poor, but China’s population had been growing for centuries as a result of the adoption of a variety of rice that could yield two full crops per year, effectively doubling the amount of calories available from rice. There will be a lot more to say on this topic in a future post.

[6] And this doesn’t even begin to touch on the changes in cuisine brought about by new-world crops like tomatoes and sugar. Can you imagine Italian food without tomatoes? Well, up until the 16th century you would have to. And although sugar was not a new-world crop, without the colonization of Brazil and the Caribbean and the labor of enslaved people, Europe would never have developed such a sweet tooth.

[7] Really, I don’t want to minimize the scale of this monstrous tragedy, nor do I want to perpetuate inaccuracies about the slave trade here. In fact, the transatlantic slave trade is one of those areas of history that is ripe for the type of elaboration that I’m advocating for here.

[8] Apologies for the very first-world and American-centrism of this example. It’s been a long couple of weeks.