I hope that I have convinced you that history is more than just a series of facts, but even if I haven’t, we still need to consider where these facts come from. A smart-alec will say, “books,” but that still leaves us with the question of how that information got into the books in the first place. Most of the facts that we find in history books, especially textbooks, will come from a variety of sources, but these sources fall into different categories or types. The four basic types of information that you are likely to find in a history book are:

- Historical information, which comes from texts

- Archaeological information, which comes from the remains of things that people made, also called material culture

- Anthropological information, which usually comes from examining existing groups of people and making analogies to the past

- Scientific information, which comes from analyzing data that is collected using contemporary technology and techniques

One of the most important skills that you can develop as a student of history, is recognizing which types of facts you are looking at, and thinking about how your knowledge of these categories might change the way you understand what you are learning about the past.

Historical Information

Since this is a book about learning history, it’s probably best to start with historical information. Most historical information comes from texts, although that word can have a pretty broad meaning. For art historians, paintings, sculptures and other forms of visual art can be texts. Music and film can be texts, although you won’t find any examples of the latter from ancient or early modern history. But wait, you might be thinking, I’ve seen excellent films about the past, and not just those starring Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves.[1] There are many wonderful films about history, but most of them are not the sort of sources that historians would use as the basis of history, which brings us to a VERY important distinction in types of historical sources.

Most, but certainly not all, original historical writing is based on primary sources. These are texts written by people who lived at the time that the historian is writing about. So, a primary source from the American Revolution would have to have been written around 1776, and primary source about the Ottoman capture of Constantinople would come from around 1453. Movies, (or “films” if you are a bit more snooty about them), don’t come into the picture until the late 19th century, so they can only be considered primary sources for the time they were made.

For example, if we take the film 300 a 2007 movie about the battle of Thermopylae based on a comic book from 1998, and try to use it as a primary source about the actual battle, which took place in 480 BCE, we’ll be in a heap of trouble. For one thing, the movie is fiction based on another fictional account and has only limited relation to actual events. For it to be a primary source, there would need to have been movie cameras set up in Thermopylae in 480BCE filming the actual battle, and that would have required technologies that the ancient Greeks and Persians, for all their cleverness, did not possess.[2] If we want to use the film 300 as a primary source to learn something about 2007, for example why such a movie would resonate with American audiences after six years of war in Afghanistan and three years of war in Iraq, or about homoerotic imagery and Orientalism in the early 21st century, or even why American film audiences were comfortable with ancient Greeks being played by British actors using their British accents, then we might be on firmer ground. For a primary source on Thermopylae itself, though, we’re going to have to go back a little further, to one of the fathers of (Western) history, Herodotus.

Most of what we know about the battle of Thermopylae, and the Persian wars that it was a part of, comes from Herodotus’s book, The Histories, which was probably completed in 425 BCE, or thereabouts. Herodotus himself was born in Halicarnassus around 484 BCE, which tells us something important at the get-g0. Unless he was a very precocious 4-year old with remarkably permissive parents, we can be reasonably certain that Herodotus did not himself witness the events at Thermopylae, or anything else he writes about the Persian wars in his histories. In a number of places he makes it very clear that he is relying on the accounts of others, but there’s plenty in his book to suggest that Herodotus had a vivid imagination, and that calls into question how “factual” his history really is. If Herodotus wasn’t present at the events he describes, and we can’t really vouch for the reliability of the witnesses on which he bases his account, why do we consider The Histories a primary source? For one thing, it’s pretty much the only thing we have that is written about the Persian Wars that comes from a time remotely close to them. It’s the remotely close aspect of them that matters so much. Herodotus wasn’t there to see the things he describes, but it is at least possible that the people who reported those events to him were.

In more modern history writing, we would consider the quotations from witnesses to be the primary sources and the historian’s interpretation of them to be secondary sources, but with older texts, the entire source is usually considered primary. Returning to Herodotus, his Histories contains a great deal of reported dialogue and almost all of it was probably invented. The entire book is a primary source for the 5th century BCE, not just the questionable dialogue. With a more modern history, say a book on the Vietnam war written in the 1990s, the primary sources would be the quotations from soldiers who fought and civilians who experienced the war firsthand, and the historian’s interpretations of those quotes are a secondary source.

In a typical middle or high school history class you don’t see too many secondary sources. Most of what students get to work with are primary sources and textbooks, which might be called tertiary sources, since most textbooks are derived from the work of other historians[3]. The textbooks we know and love (or loathe as the case may be) tend to make up the bulk of a student’s experience with learning history, which is both good and bad. It’s good because well-written textbooks can provide a framework for understanding the broad strokes of what historians consider important. But textbooks can be bad if we think that they contain a complete and accurate record of what happened. They can be a good starting point, but they make a lousy endpoint. Secondary sources can be wonderful to read, and it’s a shame that we don’t use more of them in school, because if you go on to read history as an adult, you’ll likely be reading secondary sources.

As I hope has become clear so far, dates are rather important when we read history. Not only the dates of events that are being described, but the dates when the descriptions were produced. Often there are no accounts written during the time events happened, especially the further back we go, so how do we make statements about those events or phenomena. Sometimes we have to rely on analogy, but when we do, we must be cautious[4]. One example of this understanding by analogy occurs in one of the books I use to teach ancient history. In a section about pastoral nomadic warriors from the second and first millennium BCE, the authors provide a quote from a Chinese writer about the Xiongnu, nomadic warriors that menaced China in the first century CE. Not paying attention to the dates, it would be easy to assume that the description of the Xiongnu was a primary source for the earlier nomadic groups, but it’s not. When historians use sources this way they are making an analogy between a later group and an earlier one, saying in effect that the similarities between these two groups are greater than their differences. This type of argument by analogy is the essence of what happens when anthropology shows up in our history books.

Anthropological Information

It’s always useful to remember that for most of the time that humans have inhabited the planet (at least 90,000 of our 100,000 years, if we estimate conservatively) the only records that of their existence are the tools that they made that happened to survive, and their skeletons. No pictures, no writing, and certainly no written history. Until we invent time machines there is no way to know for certain exactly how early humans lived, so we must use our imaginations and make inferences about them. One way to do this would be to assume that human beings are unchanging in their basic patterns of thoughts and behaviors, so they are fundamentally not so different from you and me. But you and I can read books and we wear clothing made from synthetic fabrics and we eat processed food, sometimes that we haven’t even prepared for ourselves. And we eat sugar and coffee and all sorts of things that were unknown to our earliest ancestors. To imagine prehistoric humans as behaving just like modern ones is actually to deny their unique history.

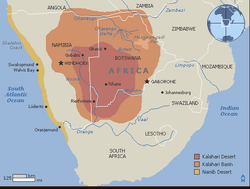

Instead historians can draw from the lessons of anthropology, looking at those foragers who still exist, or often at the descriptions of foragers recorded by anthropologists in the 19th and 20th centuries, and making an analogy between these later foragers and the earlier ones. Thus, if you want to understand what it was like for a forager in western Africa in 50,000 BCE, examine the lives of San foragers of south western Africa, or the descriptions of how they lived before many of them were forced to become farmers[5].

But there are a number of problems with this way of reconstructing the past. Most of the foraging people who have maintained that way of living have been pushed to the most marginal lands by people who live as agriculturalists or in industrial societies. It is likely that when foragers had more space to choose from, their patterns of foraging were very different. This is especially true when looking at food. To assume that foragers from 50,000 years ago lived off the same food supplies provided by the least hospitable environment such as the one where foragers are forced to live today would give us an inaccurate picture.

In addition, it does not seem plausible that current foragers have not been influenced in their ways of living by contact with other more numerous people. One of the constant features of world history is that interaction between peoples is a catalyst for change.[6] 100,000 years ago there were many fewer people (source), so it was much less likely that one group could force significant change on another. Now, even the most isolated people can still be influenced by outside groups, and it is reasonable to assume that they would be, and therefore the foraging lifestyle that can be observed today has also been subject to outside influence.

All of this is to say that our descriptions and understanding of how foragers lived is a matter of conjecture and inference. This doesn’t mean that we should throw up our hands and say that we can’t really KNOW anything about them, only that we need to be careful to remember that very little of what we can say about foragers should be taken as 100% certain. That’s something to remember about other people and places we learn about as well.

Before looking at archaeology, I should say a last (for the time being) word about anthropology. If you read enough history textbooks, especially the early sections about “pre-historic” people, you are likely to come across the word primitive, to describe foragers or early agriculturalists. You might even see the word primitive used to describe foragers or agriculturalists living in the world today, if they don’t have so-called modern technology like telecommunications or internal combustion engines or chemical fertilizers, to name a few key technologies that I would argue are hallmarks of 21st century life. Anytime you see the word “primitive” an alarm bell should go off. Few words are more judgmental than primitive, except perhaps for, “civilized” or “modern” or “advanced” or … well you get the idea. As with any description of a people who are not the same as you, it’s best to think of them as just that, not the same as you, since this will open you up to thinking about how they are not the same, why they are not the same, and what the differences between you and them say about BOTH you and them.

Archaeological Information

Archaeology is very closely connected to history, especially ancient history. Often the only information we have about complex societies from the distant past comes from the things that they left behind, especially those things that were built to last like, well, buildings. Except for inscribed walls and artifacts, understanding these objects, sometimes called material culture, requires that we make inferences about the people who created them. As we saw in the last post, we can be more confident in some of those inferences than others. To paraphrase one of the archaeology books I used long ago, it takes imagination to make the mute stones speak.

Archaeological evidence can be tricky. The first issue is that it is almost always incomplete. Although new technology like LIDAR can tell archaeologists about underground remains that haven’t yet been excavated, human beings have been building things on earth for a long time, so there’s a lot of places to look. A second problem is that we have an unfortunate tendency to build our settlements on top of old ones. Sometimes, as in the case of the ancient city of Troy, it means that there are multiple cities to uncover and the remains of one gets mixed in with the remains of others. Even worse, from the archaeological standpoint, is when a modern, still inhabited city gets build on top of an older one. Anyone who has visited Mexico City and seen the Templo Mayor right next to the cathedral and Palacio Nacional has experienced this.

Most of the inferences that we make come from the archaeological remains that we find, but we can also draw conclusions from the things we don’t discover. For example, the presence of a wall around a city suggests at least two things: one, that the city felt enough of a threat that they build a wall for protection, and, two, that the people who ran the city were able to mobilize enough resources, especially workers, to build the wall.[7] Both of those inferences seem pretty solid, perhaps solid enough to call them historical facts. It might even be that they are so obvious that historians wouldn’t mention them, but that would be a shame, because if a city were under constant threat of attack and was organized in such a way that its leaders could compel the amount of labor required to build a wall, those two facts would have been very important in structuring the lives of the people living in the city, and are definitely worth knowing and thinking about.

What about the absence of walls? It’s possible that a city lacking a wall was a city without enemies, but it would take a bit more evidence to reach that conclusion. If a thorough examination of a city’s remains revealed no walls an also no evidence of weapons, we might be on firmer ground in saying that external threats to that city were minimal, as has sometimes been said of the Indus Valley civilizations, where the cities were wall-less and few weapons have been found. As with almost all archaeological evidence, though we need to be careful with the conclusions that we draw. It’s possible that the people of the Indus Valley did have weapons, but that they were made of wood or other organic material that would have disappeared over the course of 3000 years.

Let’s stay with the Indus Valley for another example of a problematic inference that we might draw from the absence of material remains. Approximately 1500 Indus Valley sites have been discovered, but in all those sites, archaeologists have not found many structures that can be confidently identified as religious buildings. Does the lack of temples mean that the people of the Indus Valley culture had no religion? Of course not. The absence of buildings that we might recognize as religious only means that their religion did not feature the sort of religious structures that we are familiar with, so rather than seeing this as a deficit, it’s better to see it as an opportunity to look for other types of evidence to figure out, if we can, what sort of religious ideas and practices they had.

This leads us to another aspect of archaeology that might encourage us to be a little more careful in drawing historical lessons. Often the biggest and most durable structures that a culture creates served the culture’s elite more than its general populace. Temples, for example, were built and maintained for priests or other religious leaders, and not for direct use by the common people. Palaces were the homes of political elites, and forts were used primarily by soldiers. Architectural remains tend to have an elite bias that we need to remember, so while they can be especially helpful in understanding political or religious structures and a society’s values, they may not be able to tell us as much about how common people lived as we would like.

Luckily, there is a rich archaeological source that we can use to learn more about how non-elite people lived in the distant past, or if you want to be pedantic, about how non-elite people died. These are graves, and although they can feature a similar elite bias to that of architecture, we can learn a great deal about a culture from how people disposed of their dead. One of the ways graves can help us most is by using them comparatively to learn about different levels of social status. Although it’s not 100% certain, it’s reasonably safe to say that people who were buried with more goods, or goods of higher value had a higher status than those with fewer or lower quality grave goods. The amount of information that historians take from grave goods can be truly remarkable, especially when it comes to ancient history, and scientific advances are telling us more every day.

Scientific Information

Of all the types of information that goes into writing history, probably the most exciting is information that comes from advances in science. It is also the information about which I know the least and am least comfortable discussing, so this section will likely be the least detailed, and possibly the least accurate. But if you read more recent history books, you may find a number of ideas that have come out of hard scientific research and are often expressed in graphs, tables and charts using statistics. So, if you want to be historically literate in the 21st century, you won’t be able to avoid science and math (like I did when I was studying in school).

Before launching into a discussion of the new ways that science helps us understand old times, it’s necessary to remember that when we read statistical information about the past, this data are modern constructions, not primary sources describing what happened by the people who saw it. Sometimes we have some contemporary confirmation, such as the records people in Europe kept of the freezing temperatures during the Little Ice Age. More often than not, though, newly gathered scientific data can give insights into phenomena that had far reaching effects, like past climate and environmental changes, such as deforestation. It is likely that these phenomena, for example, lead concentrations in the air that can be measured using samples from ice cores, or changes in temperature that can be “read” in tree rings, would not have been available, or perhaps even visible, to people living at the time.

Sometimes, it isn’t that science has provided us with new data, but that we can look at it in new ways using statistics and mathematical modeling. One of my favorite examples of this has to do with my favorite data source from the ancient world: graves. In his book Violence, Kinship and the Early Shang State, Roderick Campbell uses statistics to make a number of interesting points about social stratification during the age of the Shang (approximately 1600-1050 BCE). The mathematics are more complex than I want to get into here, but by counting the number of graves and the amount of grave goods found in each, he makes the point that over time, more and more people were buried with a larger number and a greater variety of grave goods, but that the wealthiest people would still be found with the most and most valuable goods. From this he concludes that the as the Shang era progressed, the region became wealthier, probably through trade, tribute and manufacturing, so that more people were able to acquire and be buried with more things. He further infers that lower classes were emulating the wealthier elites by copying their style of burial. He cements his arguments with a series of tables and charts that sure do seem to support his conclusions, but the truly fascinating thing about this chapter is the way he uses mathematics to create interpretations from archaeological finds.

Sticking with graves for one last example, new scientific techniques are beginning to be used to tell us things about human settlements that may seem obvious, but couldn’t be proved until very recently. This is because we now have the capability to analyze the most important thing found in any grave, the skeleton of the person interred. Thanks to the relatively new scientific field of paleogenetics and scientists’ ability to extract and analyze DNA from ancient skeletons, a 2019 study in the journal Science, argues two things that strengthen our understanding of social stratification among a group of ancient settled agriculturalists in Bronze Age Europe. The first thing their analysis reveals is that wealth was indeed kept within families, since the bodies in the graves with the greatest amount of funerary goods were genetically related to each other. They were also, surprise, males. The other fact that the scientists brought to light was that these early Eurasians practiced exogamy, they sent their young women away to be married and the men in this settlement brought in women from elsewhere to marry. We know this because the female skeletons that they have analyzed are not genetically related to any of the males, whereas the males were related to each other.

As with almost any of the conclusions that have become or will become historical “facts,” we need to take some of these new scientific findings with a grain of salt. After all, the scientists have only been able to get workable DNA samples from a small number of skeletons. It’s possible that more sophisticated analysis will poke a big hole in the conclusions about exogamy. This new way of looking at the past, using tools that were unavailable even thirty years ago is incredibly exciting for history, particularly ancient history, even as it makes learning about the past much more difficult.

Conclusion

The challenge for students and anyone else who wants to better understand the past is the one that this post invites you to seize. New technology has enabled us to find more information, and new perspectives on what matters in the past have led us to look for information that in the earlier eras wouldn’t have been considered important. As we gather all this new information, whether from scientific and statistical analysis, searching for new texts and material culture to study, or re-examining our assumptions in light of new or different theoretical perspectives, it is so much more important to try to examine not just what we know, but how we decide that we know it. Asking the question: “How do we know that?” about the past has always been crucial to learning history. Now, however, there are more answers to that question than there ever were before. So, as you continue in your endeavors to learn about the past, I wish you luck and perseverance, because you’re going to both.

[1] Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989). Look it up, you philistines.

[2] Now, I suppose it is possible that the Greeks invented movie cameras, one of my film studies professors tried to make the point that Plato’s cave is the original movie theater, but it seems highly unlikely for many, many reasons, and even if they had invented movies, they would also have had to invent a storage system that would preserve celluloid film for 2500 years for us to see the actual footage. I’m not holding out hope that an archaeologist is going to find it.

[3] I don’t know what you would call this post. A quaternary source? A meta source? I’m open to suggestion.

[4] Like visiting a cantina in Mos Eisley – level cautious. Maybe even more.

[5] I chose the San as a representative example of foraging people because they are relatively well known and have been studied as a model of foragers. They are not the only group that could be used as a representative example.

[6] Quiz time: What kind of a fact am I presenting here?

[7] More on this in a later post on power and how (I think) it works.